Inspired by a post on James Reasoner’s Rough Edges blog. Cover by Wesley Neff, interior illustrations by multiple illustrators.

|

| Adventure, March 1940 - cover illustration by Wesley Neff |

An excellent story from Surdez – not one of his Foreign Legion stories. It’s a story of the French army at the beginning of World War 2, confident in the ability of the Maginot line to defend their country, with the memory of the past war a pale shadow in the minds of the young men who joined the French army at the beginning.

Brunot, a veteran of World War 1, watches the young soldiers of France join up. He has honors from WW1, but he has chosen to serve as a mechanic. The fresh troops think he is an outmoded grandpa who doesn’t understand the present world, and make fun of him. He has a moment of glory as he crushes the hand of a corporal who insults him, but the moment of glory is brief as the troops gang up on him. He starts to hate the French troops, but then the Germans attack…

An insightful character study from Surdez, and Brunot is a great character. Worth reading.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - The Knight of Old by Georges Surdez |

“Germaine, Ger — maine! The sergeants are waiting for the gudgeon! It’s ready! Be sure to draw their wine!”

He found a free seat, in an angle near a window. Between the red cotton curtains, he could see the green hills, a stretch of road lined with plane trees. That was Germany, over there, and the quivering of the glass panes in the frames was caused by the discharges of distant artillery. When Brunot had seen this Moselle region last, he had been in uniform already.

But he had been as young as that slim corporal of Chasseurs, so trim and soldierly in his khaki capote, who was kidding with the girl, a beefy, reddish wench, with a broad, flat face, a moist smile and eyes round, lustrous as a heifer’s. The fat woman kept calling, but the war was too new for her to be organized on the right mental level; the attention of these young men pleased her immensely. Brunot shrugged. She would discover before very long that soldiers admire and desire when and where they may.

The technical descriptions of oil exploration are great, but the story is driven by an improbable romance. The murder mechanism is over elaborate.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - High Explosive by J.J. des Ormeaux |

WE MUST have looked as though we were crazy. But that’s the way shooting crews always look. There were six of us, stripped to the waist, up to our knees in water and muck on the near shore of the bayou. Six of us, in two fans of three, like a backfield formation, with room enough between us for a truck to pass.

Across, on the far shore of the bayou, we could hear the truck, hurtling through the underbrush with a noise like a threshing-machine. I got a glimpse of the truck’s red cab, through the tangle of scrub and cypress, with the High Explosive signs on top of the cab swinging crazily.

That truck must have been doing fifty-five. It burst out of the trees, headed for the bayou. The bayou was about twenty-five feet wide and looked like a flower garden. This was because it was choked with water lilies and purple hyacinths, the curse of waterways in the deep South. There was a hogback in the middle of the bayou that stuck up like the black back of a whale. The half-ton truck hit the water like a hydroplane, seemed to skate across those hyacinths, and hit the hogback. Here it hesitated.

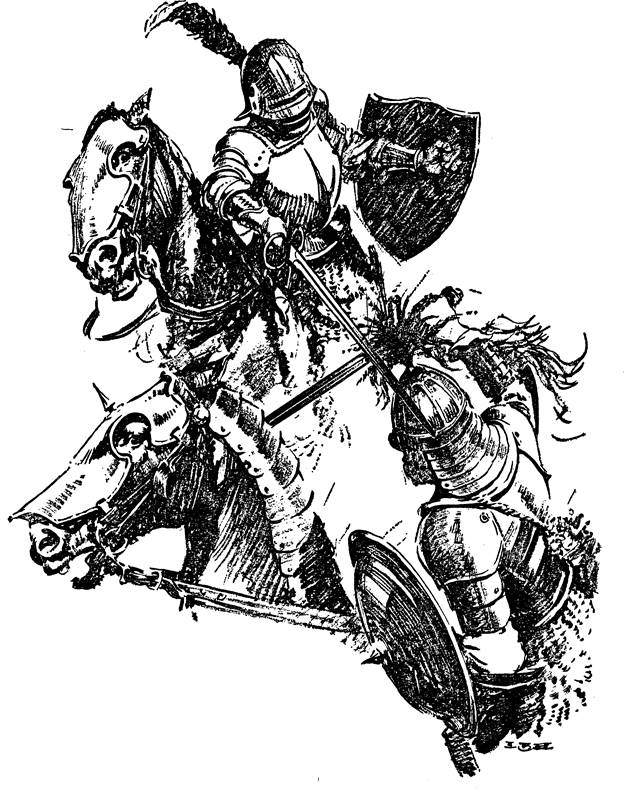

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. The invasion was completed in a month, the Russians and Germans divided Poland between themselves. With this fresh in his readers’ minds, Bedford-Jones reached back to the 1400s when Poland defeated Germany in the Battle of Grunwald.

This story could have appeared in Blue Book as part of the Arms and Men series. Bedford Jones contrasts the horror of modern warfare with the knightly behavior of the past, but still manages to build up the image of the cowardly lying German invader.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - The German and the Pole by H. Bedford-Jones |

“IT DOES not matter particularly I how a man lives,” said the man dying on the bed. “The important thing is how he dies.”

To Morton, the company surgeon, this was a novel point of view. He stared thoughtfully at the speaker, who had been frightfully cut up in an accident at the tannery. There was nothing to be done for the man, who had chosen to die here in his own shack rather than in the makeshift company hospital.

“I should think it’d be the other way around,” observed Morton. “Life’s the greatest thing to any of us, after all.” The man on the bed smiled and shook his head. His face was bright and hard under big sweeping mustaches. He was a Pole, like most of the tannery workers, who here in the north Michigan woods made hash of the hemlock bark. His name was Sobieski, a common Polish name.

“No, doctor,” said Sobieski. “All men die. When years come upon you, then you remember how your father, your mother, your friends, died. You reach back and recall how the great ones in history died. In time of war and terror, as in Germany and Poland and China today, the thought of death is close. Will you reach up and tap that drum for me?”

Morton’s sole duty now was to humor his patient until the inevitable end came. Also, he was interested in this tannery worker, who had ideas, who spoke good English, and who was all alone in the world. He looked up at the thing hanging on the wall, and rose to obey.

The shack was bare and ugly, with no comforts. On the wall hung a crucifix; except for the drum hanging there, no other ornament appeared.

Nor, thought Morton, was the drum particularly ornamental. It was queer. It was dirty. A big round drum of metal, like a basin, a drumstick with padded end hanging beside it. This, too, was so dirty that Morton shrank from touching it.

No review because this is not the first part of the serial.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - Quantrell's Flag by Frank Gruber |

THE war between the states, the conflict which had been inevitable for so many years, had broken out, and an over-confident Union, prepared for a quick conquest, had seen its armies hurled back to Washington by the defeat at Bull Run.

To Doniphan Fletcher, newly graduated from West Point and awaiting his commission, war was no stranger. They had been fighting in Missouri, his native state, for years—border ruffians, raiding Kansas, and Kansan Redlegs and Jaw-hawkers pillaging Missouri in bloody reprisal.

Now, Donny Fletcher had decided to go back to his home state and do his fighting where his home and family needed him.

“High and Outside!” · W. C. Tuttle · ss 2.5/5

Tuttle had recently become president of the Pacific Coast Baseball League and the story seems to be one of a pair based on Tuttle’s experiences of players becoming umpires. |

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - "High and Outside!" by W.C. Tuttle |

Mr. Bill McColl Fresno, Calif.

Umpire Majer Leeg March 15.

New York City.

Dear Bill:

I will bet you will be supprised and laugh when you rede this letter. Remember the old days on the Coast when I used to fog my high hard one rite down the old aley and you used to duk and yell ball? I never could figger how you ever got into the Major Leeg unless they needed somebody to take the conseet out of pitchers.

I always figgered that if I ever become a umpire I would sure give pitchers a brake (especially left handed ones with my ability.) Well, I am, Bill. I finely got tired of having umpires call my strikes balls, so I quit and got a job on a truk in Fresno hauling things at twenty-five dolars a week. It ain’t big money, but I took the job when they told me that there ain’t no umpires working as hiway cops. See what I mean, Bill?

I remember you used to laugh at my smart remarks when you said that my three and two ball was six inches outside and the winning run walked in. It was more or less of a snear than a laugh. Well, like I said I was driving a truk when I heard about this new Sundown Leeg. I could a applied for a job pitching and burnt up the leeg in a week, as you know, Bill. But I got to thinking…

An average story from Luke Short, about an aspiring inn owner who wants to just do his job without taking sides among his clientele. It’s set in the early days of the west, when might is right, and Goliath kicks the ____ out of David more often than not.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - The Fence by Luke Short |

THAT summer the railroad built a spur from Reese to Sevier Valley, and by fall they had lost two bridges trying to span the quicksands of the Roaring Fork. Charlie Kextel, whose tent saloon had followed the main line railroad camps to the coast and was now working the spurs, saw what was coming back in mid-summer, and he took a careful look at the country. The long grama grass flats suited him and the Silverbows to the east and Cecil Mountains to the west were pleasant enough, so he hired some men to cut and haul logs to the Roaring Fork.

When the railroad’s second bridge went out in the wide flood of the Roaring Fork and it was evident that they couldn’t reach Yellow Jacket before the snows, Charlie Kextel’s big log building by the river was finished up to the eaves and axemen were cutting away the overspreading cottonwood branches to make room for the roof.

And by the time word had been received to quit for the year and the railroad had thrown up a way station and some stockpens and put in their derail for the winter and pulled out, Charlie’s place was done.

It was a big building, set back a spell from the tracks; its lower story was a saloon and restaurant, its upper story a hotel. He sent word to his wife to come and bring a girl with her, and while he was waiting for them he built the warehouse by the tracks and the first rider came in for his first drink. He didn’t come the way Charlie expected he would come or wanted him to come, but he came, and afterwards Charlie knew he was in for something.

A railway story of hobos from A. A. Caffrey. Not my cup of tea.

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - The Stretcher by Andrew A. Caffrey |

There were two railroad bulls standing out there on the crossing. A couple of town coppers stood back near the gates. Of course, the railroad bulls were on hand to see that no free-riders hopped that freight, or even made the try. And the town cops had the same idea.

Julesburg, at the time, was sort of hostile to drifters, and if a hobo reached for a grab iron while the Law was in view, he’d best make sure of that grab, or else! Fact is, the Law was taking means to warn drifters against riding ’em. And they were doing the “warning” with boot, bat and outright, up-the-track brutality. So the game was pretty tough.

Well, you’d say that the Law need have no great worry about drifters making that freight. Also, you’d guess that no drifter would be silly enough to make the try. Not if the drifter in question knew anything about rolling stock when it’s really rolling.

Because this fast freight was really on the move, sucking and rolling so much dust, dirt, tumbleweed and right-of-way junk along with it, that everybody, including the railroad and town cops, was sort of standing back, away from the immediate dusty neighborhood of that through rail. That main crossing in Julesburg is pretty wide, and that eastbound train was going by on the far rail. This left a good-sized stage for operations between the onlookers and the roaring, humping, clanging string of U.P. freight cars. And out onto that wide, free-space stage, as though he owned the world, strolled a tall, thin feller.

The Camp-Fire · [The Readers] · lc

|

| Illustration for Adventure, April 1940 - The Camp-Fire |

NEWCOMER, and most welcome, to our Writers’ Brigade, is J. J. des Ormeaux, with the novelette, “High Explosive.” His account of himself includes such matters as—does a cow like dynamite? of course it does—and the rest you may read for yourselves as follows:

My life was humdrum enough, college, a little travel, a little starving trying to sell fiction, until the depression came along and blew a cold blast on my budding literary career and booted me a large and healthy boot halfway across the country into seismograph work. The oil industry didn’t seem to be suffering any depression; at least they were putting down wells all over the Gulf Coast and seismograph crews were plunging through wildernesses and swimming through swamps trying to show them where to put more. “Doodle-bugging,” as this exploration work is called, I soon found to be one of the few happy-go-lucky, hell-and-high-water. adventurous occupations there still are in the country.

Everything happens on the job from being stalked and potted with a shotgun to having cows eat the dynamite for its salty taste. It’s excellent training either for guerrilla warfare or being a gypsy. You’re here today and gone tomorrow, maybe to a swamp that even the Army Engineering Corps has given up as a bad job after marking a few vague dots on the map, maybe to a boom town where ten crews are after the information you’re after, maybe to California, Venezuela, Rou-mania. It’s a job that has its dangers—a whole crew was blown up not long back; its diversions —the local girls, local dances, local beverages; its reward—discovery of a dome.

Any professional “doodlebugger” will recognize the simplification in the story, necessary so as not to bog down the narrative with technical details. For example, a dome is in reality a tremendous plug of salt, usually pure table salt, upthrust by tremendous pressure from the ancient sea-bottom, and the trapping of oil results from the cracking, fracturing and splitting of the rock layers in its path.

In the years I was on a crew, having been everything from a helper to crew boss, I don’t believe I ever had so much fun in my life. Certainly not since, in the adventures I’ve cooked up in fiction, have I had anything like what we used to have on the old crew.

Ask Adventure · Anon. · qa

The Trail Ahead · Anon. · cl

Starting in the 1940's ADVENTURE had many stories about WW II and Surdez was one of the best writers covering the war. I'm glad to see a link to Hamilton Greene's career because he was just about the best artist covering the war. At this time the magazine started to use several illustrations for the longer stories instead of just one.

ReplyDeleteAgree with you on all counts, Walker. This being an early 40s issue, war stories hadn't entirely taken over the magazine and the Surdez one in this one isn't one of the usual run.

DeleteThe change of including multiple illustrations was a major improvements over the Hoffman era Adventure, great as it was.